Looking into the polychaetes species of Singapore

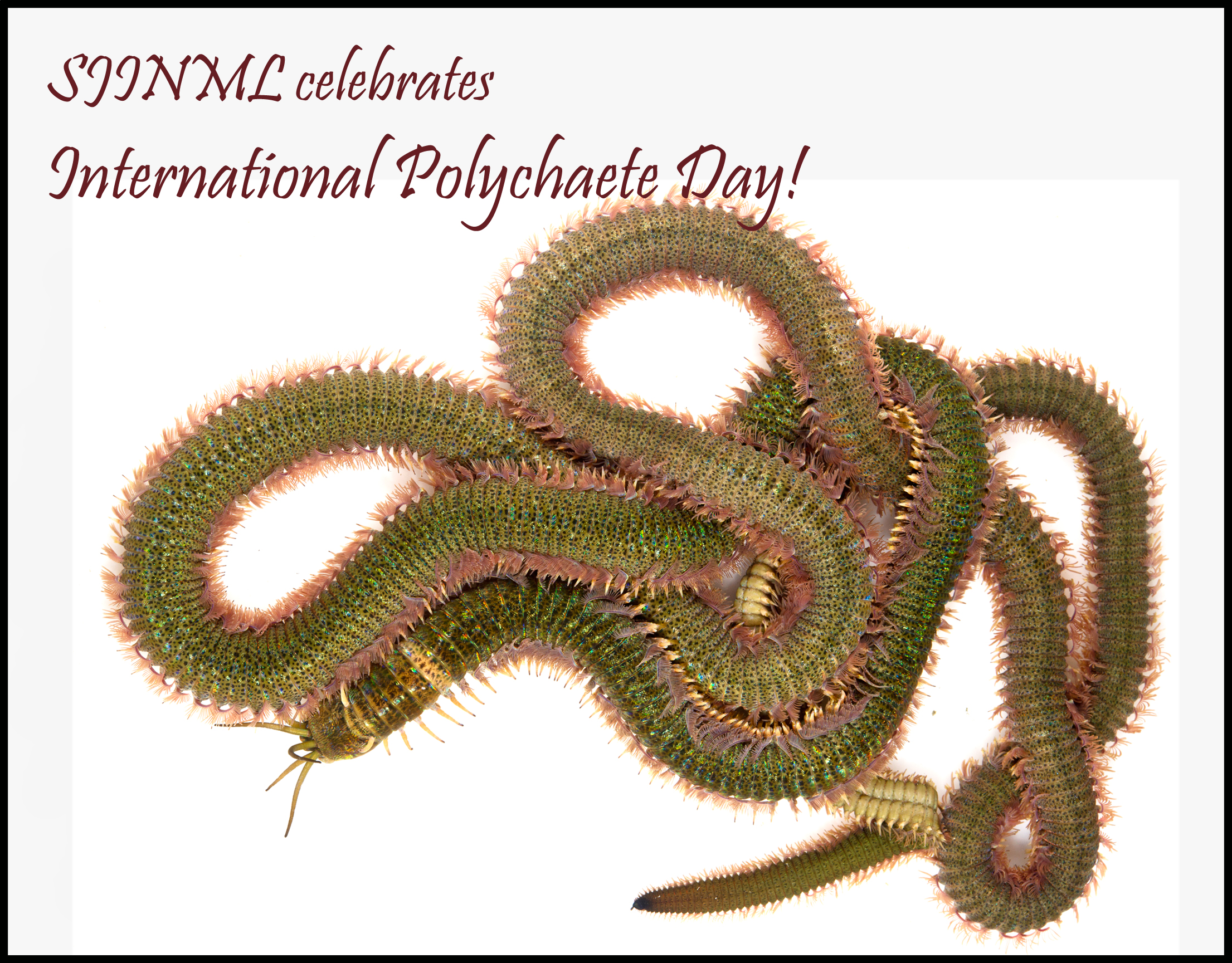

In this four-part series celebrating International Polychaete Day (1st July), we will feature four different polychaete research carried out at the St John’s Island Marine Laboratory. We are kicking it off with a subject closer to home ― the biodiversity of polychaetes in Singapore.

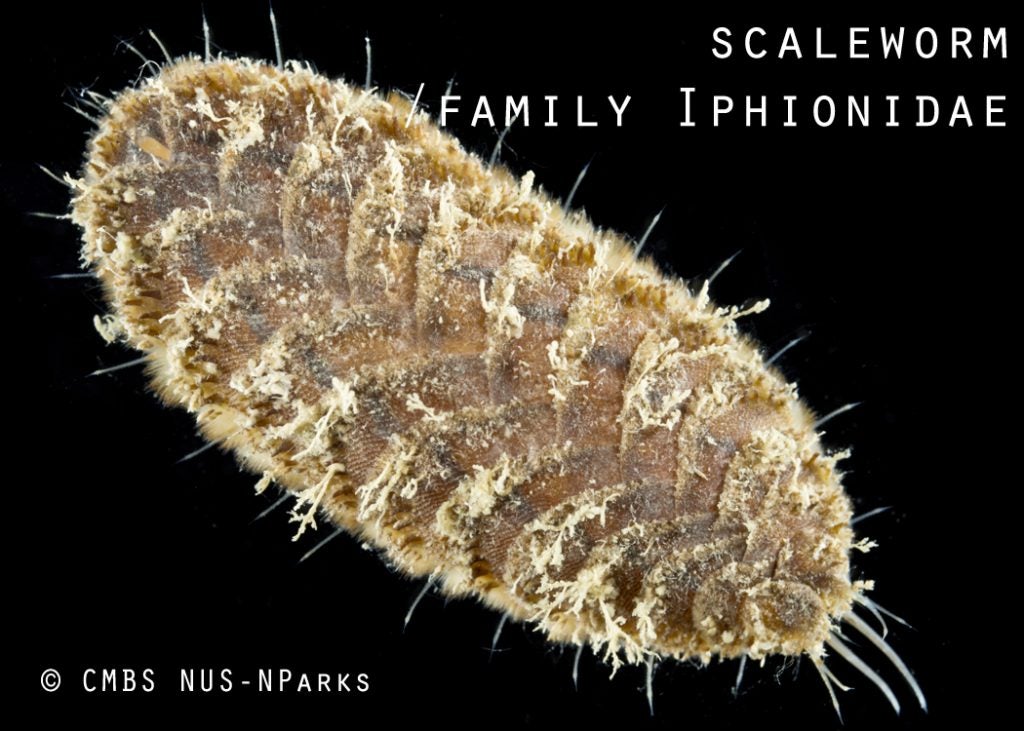

If you have heard of bloodworms, bristleworms, fanworms, feather-duster worms, fireworms, ragworms, scaleworms, sea mouse, spaghetti worms, tubeworms, would it surprise you that they are all actually polychaetes!

To date, 90 species of polychaetes have been recorded from Singapore. Local scientists are still discovering new records for Singapore and possible new species. A large part of the current research is based on specimens collected during the Comprehensive Marine Biodiversity Survey (CMBS), conducted jointly by the National Parks Board and the National University of Singapore in 2010 to 2015, and supplemented by earlier specimens deposited with the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.

The diversity of species found in the northern coast of Singapore is different from the southern islands, largely because of the differences in sediment types. The large tracts of muddy habitat in the northern coast of Singapore are perfect for ragworms or Nereididae species, which are able to move well in loose organic particles and are detritus feeders. On the flip side, reefs and sandy shores of the southern islands are home to tube worms and burrowers, especially species from the Eunicidae family.

The species Neanthes glandicincta is the most abundant and common in the mudflats along the northern coast, such as at Sungei Buloh Wetlands and Kranji mangroves. Birds that stop by the wetlands during the migratory season of October to January are likely to feed on these worms. When the worms become sexually mature, gametes (eggs or sperms) are stored throughout the body. This causes the usual pink translucent skin to appear either green (for females) or yellow (for males). Their feet also become more pronounced and longer to help them swim to the surface of the water for aggregate spawning.

Did you know that there were seven species of polychaetes originally described from Singapore? In fact, four were only discovered in the last 20 years along with an increase in taxonomic effort. Neanthes wilsonchani was the most recently described in 2015 and might have diverged from Neanthes glandicincta due to the different geological constitution at the eastern Singapore.

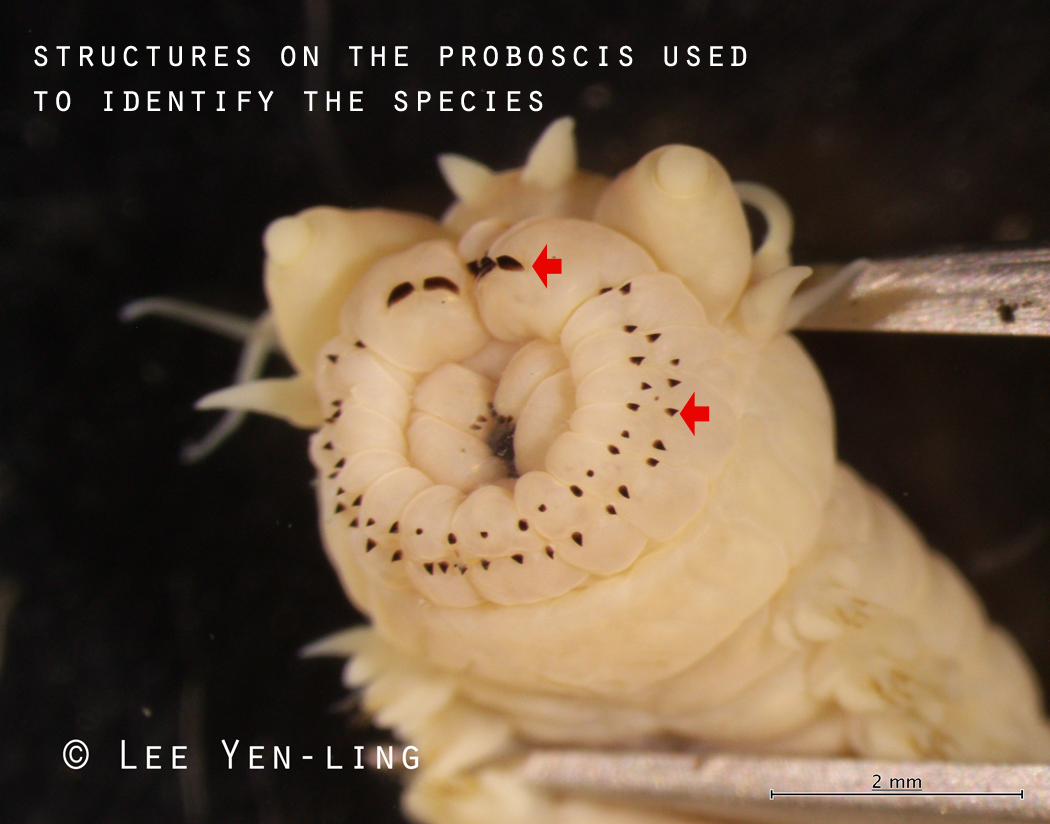

Another Singapore species, Perinereis singaporiensis, was described by Prof Dr Ed Grube in 1878 in his work Annulata Semperiana. It is rare but could be found at both muddy and sandy habitats. The live animal has a dark shiny torso. Belonging to family Nereididae, it has a muscular proboscis that it shoots out when feeding or in defence. The proboscis have hard structures called paragnaths made of chitin or scleroprotein, or soft structures called papillae that look like small bumps or triangular extensions. These small structures provide important clues to the species!

The current records represent just the tip of the actual polychaete diversity in Singapore as taxonomic work on species from inaccessible habitats has only just begun. Knowing where different polychaete species could be found will help us understand sediment health, nutrient availability, and can be indicators of environmental pollution.

Contributor: Lee Yen-ling

In the next instalment of this series, we will talk about research on culturing polychaetes. Stay tuned next Wednesday!

Come follow Singapore polychaetes research on

Twitter: https://twitter.com/SPolychaetes

and follow the celebrations on